The history of the armada begins many years before 1588. In history, the roots of any issue go back essentially as far as humanity - but we like to keep the stories shorter than that. The story of the proposed invasion of England has to do with the great dynasties of renaissance Europe. England (later Britain) has a magnificent past of battling with the great houses of mainland Europe, especially two of the most powerful: the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs. Again, this tale could go deep into the annals of lineage and shield...ery. But I'm not that smart and you have better things to do. We're going to start this tale with an introduction of a man named Philip.

Philip was born in Valladolid, Spain, in May, 1527, the son of the mighty Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain and a Bunch of Other Stuff, Charles V, then-patriarch of the powerful Hapsburg dynasty. A number of factors helped shape Philip's development, and this is really the genesis of the story.

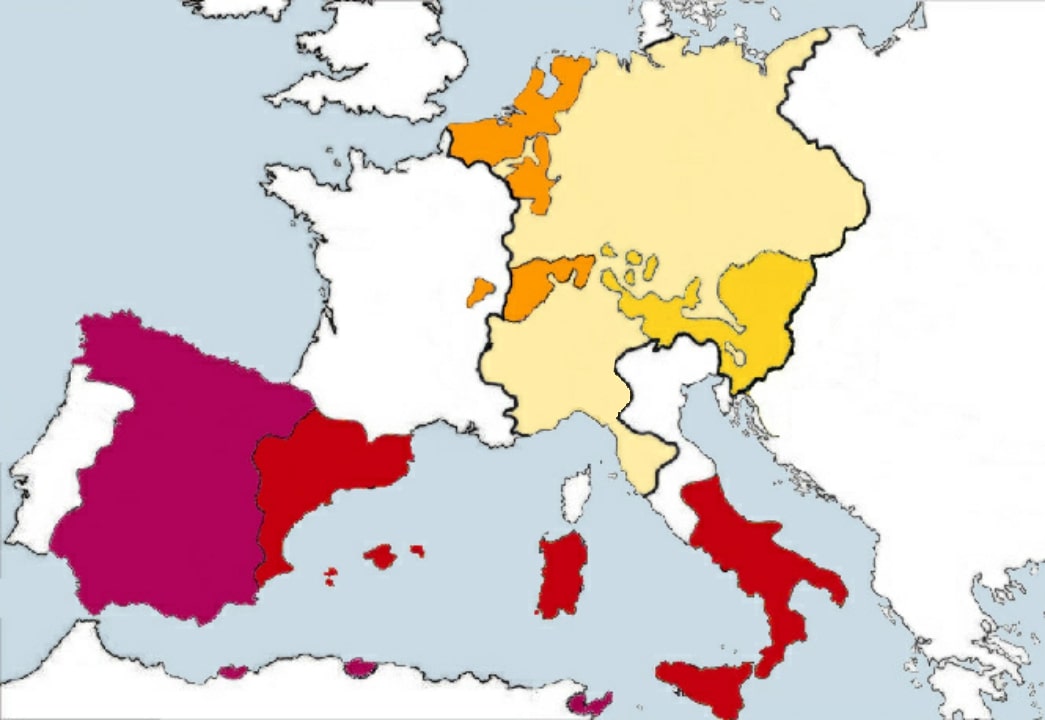

Philip was born in Valladolid, Spain, in May, 1527, the son of the mighty Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain and a Bunch of Other Stuff, Charles V, then-patriarch of the powerful Hapsburg dynasty. A number of factors helped shape Philip's development, and this is really the genesis of the story.One thing that the Hapsburgs were good at was getting to be king of stuff. I joked earlier about Charles' holdings, but the joke is based on fact -- at various times Charles ruled massive chunks of Europe: Spain, Burgundy, Flanders, Austria, Germany, Italy, Naples, Sicily, you name it. Charles made the power play of a lifetime when in 1554 he wed his eldest son, Philip, to the 37-year-old Queen of England, Mary I, "Bloody Mary."

This would have been a huge opportunity for Philip. He would not really get to be king of England, just play at it. He would co-rule with Mary for the duration of the marriage, which was not necessarily 'til death, thanks to Mary's father, Henry VIII. Additionally, Philip would, presumably, get to father a child by the Queen of England, entrenching a Hapsburg on the throne of England and making the Hapsburgs the most powerful dynasty this side of the Ming China Zhus.

I mentioned multiple factors, though, and the fact that Philip got one butt cheek on the throne of England was but one of them. Another was that, from his birth, he was promised the world. It was Charles' intent to have Philip inherit his throne as Holy Roman Emperor and King of Everything when he retired, but very early on, Charles' meddling brother, Ferdinand, had other ideas. Ferdinand was very popular with the princes of Germany and Eastern Europe, the same men who got to vote for the Holy Roman Emperor. He was the son-in-law of King Vladislaus of Bohemia and Hungary and was elected king of the Croats. His influence came in handy when, in 1531, he was elected King of the Romans, which was basically the title of the Emperor-Elect or Crown Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, despite the fact that Charles had already named an heir. Charles would remain in power until his abdication in 1556, meaning that for about 25 years, dinners were very tense in the Hapsburg household.

On one hand, Charles (and presumably Philip) wanted the majority of the power to pass lineally, to Philip. Ferdinand, however, was the elected protector of much of Eastern Europe, and had been elected the successor to the Empire by the German princes. Charles brokered another deal for Philip. Upon Charles' retirement, the Empire would pass to Ferdinand. The next successor to the Empire, however, was to be Philip, not Ferdinand's son, Maximilian. Upon Ferdinand's death, Philip was to take the empire, allowing Maximilian to become King of the Romans and heir apparent to the empire.

It shook down quite differently, however. As expected, in 1555, Charles left his Spanish Empire to his son, Philip, and the Holy Roman Empire passed, as agreed upon, to Ferdinand. While much more went into this discussion, the German princes worked hard to debase Philip as an Imperial claimant, and in the same year he ascended to the throne of Spain, Philip sensed the tides of change, and relinquished his claim on the Holy Roman Empire. Feeling thoroughly cheated, Philip never would get to be King of the Romans, and never tasted the throne of his father's Holy Roman Empire.

But, hey, you win some, you lose some. Losing out on the chance to be the most powerful man in the world probably didn't thrill Philip, but he was in charge of the budding Spanish Empire, and he still had that thing in England going for him.

Except he really didn't. We mentioned earlier that Philip's English kingship was dependent on Mary being around - he was king only as long as he was married to the queen. In 1558, just as everyone was sorting out their roles after the great Charles' retirement, Mary died, leaving no heirs.

Philip was so heartbroken by his wife's death that he immediately proposed to her younger sister, Elizabeth I, his only real chance to stay in London. It didn't work, and he was rebuked. On a side note, the relationship between Philip and Elizabeth is pretty fascinating. The rebuke likely hurt Philip's pride, but he continued to be amicable with Elizabeth, standing up for her to the Pope himself when the holy man wanted her excommunicated as a Protestant. However, their relationship was to prove rocky, and for largely religious reasons (the failed proposal probably didn't help), they would find themselves embittered enemies.

And so, by the mid-1550s, we have a man, Philip, who was supposed to be the most powerful man, perhaps who ever lived. The King of the World. And yet, one way or another, he had had his various titles stripped from him - or as he might very well have believed, stolen from him. His uncle and cousin conspired to snatch away the Empire, and the Protestant whore queen of England wouldn't let him rule her people, either. What we are left with is a slighted man with a very personal enemy, and the power of a world-leading nation at his disposal.

As is often the case in history, we can here ask ourselves, 'What would I do? What would you do?' The problem with asking these questions is that the issue becomes subjective, which is something we don't want. We are inclined to give ourselves the benefit of the doubt. Of course, we would take the benevolent route, the logical route. But, people are vain. People are selfish. And Philip did what many people would do - he set out to get what he believed already belonged to him.

No comments:

Post a Comment